Diving into Berghain

by Amy Liptrot

Years ago, someone told me that the best way to get through a crowd at a nightclub or concert is to dance your way through. The bodies around you will have more sympathy for a dancer – they’ll shift and accommodate, flex and bend – than for someone simply pushing.

I remembered the advice this midsummer, at a techno club where not only were most other people intoxicated but also speaking German. I was disoriented, but the best way through my discomfort was to dance. On the dance floor, I had the sensation that we were deep underwater, swimming in bass. The dancers were seabed beasties: crabs and anemones. I could luxuriate in the strangeness, in the beat, my arms floating up, light and smoke caught in the bubbles.

A lot of my 20s were spent in discos and bars and clubs. The nights got wilder, then worse and I ended up in rehab. I had not been back to a club for four years but, this summer, I planned a field trip. I would make a controlled scientific excursion to a nightclub. On the solstice, I would go, sober and alone, to Berlin’s famous Berghain, a techno club with a 1500-person capacity, housed in a 1950s electrical plant. It was built when this section of the city was East Berlin, part of the GDR.

I’ve been living in Berlin for nine months. I’ve been writing, reading and working in a warehouse and trying to learn some German. I’ve been walking a lot, clutching a small bottle of Coke, gliding around my new city guided by my phone. I went to look at a flat and went to a street with the same name on the wrong side of the city – the old west, rather than the old east. I’ve been cycling over cobblestones and looking for birds. I am happy and lost and sometimes have this lurching homesickness in my stomach.

For the last three years, before I came here, I’d been living back where I grew up in the Orkney islands in the north of Scotland. I spent my time there relearning the landscape and rebuilding myself: swimming in the sea, watching seabirds, taking boat trips to small islands. I went snorkelling and was amazed by what I saw in cold Scottish waters: exotic colours, brighter below the surface than above and wonderful creatures such as sea slugs and urchins. I regained some wonder at the world and the sea helped me in my sobriety. Now, I want to apply the things I’ve learned about nature observation to the city and to people.

Berlin is 600km from the ocean and often, because the sea has become so important to me, I wonder why I have moved here. In most of my Facebook profile pictures, I am on the edge of a cliff or entering water. How can I find these places in Berlin? Unmoored and drifting far from home, I am seeking the sea in a landlocked city. My friend Karen sent me some seaweed held in resin, so I carry the ocean around my neck. And I have been finding water where I can: visiting swimming pools, lakes, saunas and even a flotation tank, but I did not expect to find the sea in a techno club.

***

It’s midsummer’s day, the height of the year, and I am wearing my seaweed necklace as I approach Berghain. It’s Sunday evening and the party is still continuing from the night before. I have a notebook and am incognito in black clothes. The building looms above, huge like a container ship, and I am nervous. I learned that sailors wore one gold earring to pay for their funeral if they were washed up on a strange shore and now I too am entering dangerous territory.

The club has a notorious and mysterious door policy that sees scores of people turned away every night. The guy in front of me is unlucky – perhaps too drunk – and the stern doormen shake their heads and he walks away resigned. But they let me past and I text my friend, “See you on the other side”.

Berghain retains many of its industrial fittings and as I climb the steel staircase to the main room – the old turbine hall with a high ceiling and concrete floor – the noise hits me. The immense volume of the music creates a full-body experience. It makes my chest throb. It’s loud enough to swim in.

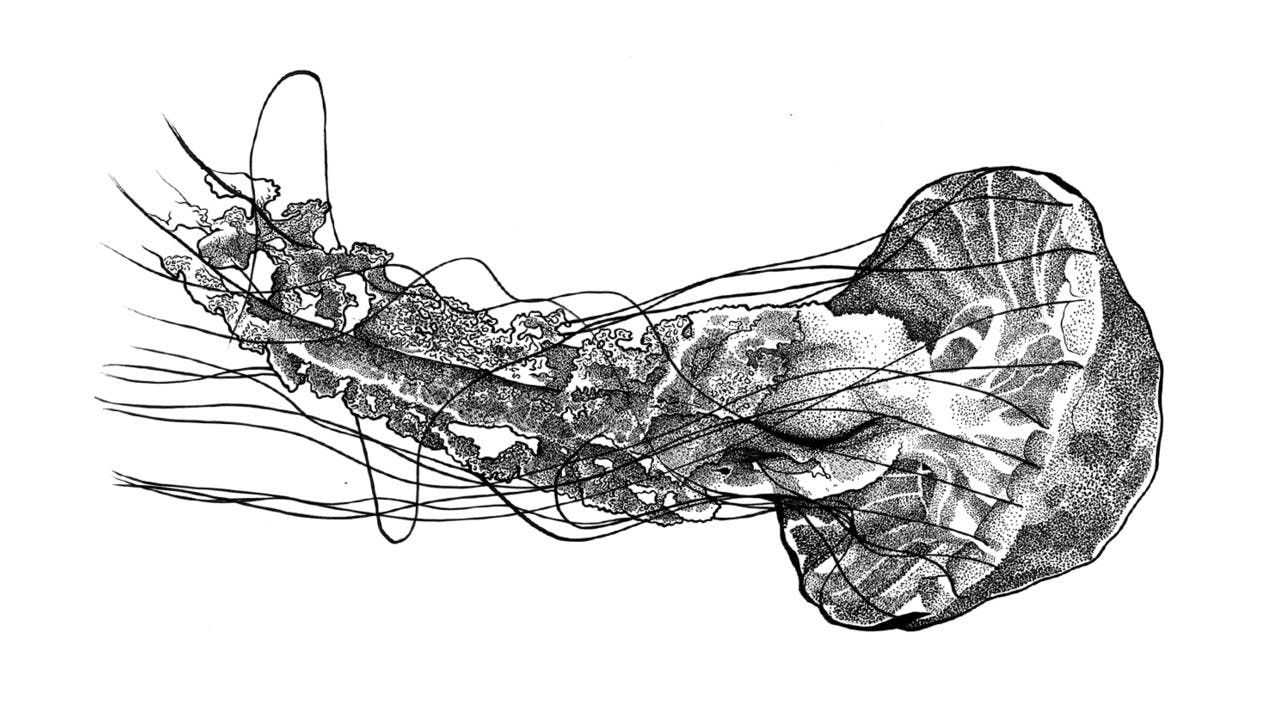

Entering this place is like swimming into a vast, echoing cliff cave and, once my eyes adjust to the dark, finding it full of rock doves and black cormorants, on shadowy ledges, darting past. I’ve found a complete ecosystem. Five hundred people or more, a bloom of jellyfish, are drifting with the tide of music. Exquisite creatures appear from behind pillars and speaker stacks like rocks: fashion goths and techno gays, in leather and mesh and Lycra and neoprene and swimsuits, every type of black. They are dancing with fans, topless in chain mail, showing off their tattoos. I am reminded of the beautiful and weird illustrations of Ernst Haeckel, the German naturalist and philosopher who, at the beginning of the 20th century, made detailed studies of sea life including technical drawings of jellyfish and anemones.

Underwater, sound travels faster and objects look slightly magnified. Due to the refraction of light in water, they appear closer and larger. A similar affect is created in a club due to the smoke machine, the dark and the drugs. It is hard to tell distance, time or direction. I’m swimming in murky water. A white spotlight is like a shaft of sunlight reaching down to the seabed. There are red lasers and green exit lights. I can’t tell how long I’ve been here.

***

The people who first settled on this riverbank in the seventh century named the area “Berl”, after a Slavic word for swamp. The city is inland but an average of just 35m above sea level. Huge pipes pump groundwater out of construction sites. Buildings battle against sinking and floods. The city has plenty of water – it’s just below ground, and in the months I’ve been here, I’ve somehow been divining it.

Hanging in the toilet of a church hall in Schöneberg, where I was attending an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, was a photo of sea pebbles – pink-striped and distinctive – that resembled, or maybe were, the stones from Rackwick Bay in Orkney. The sea keeps finding me. In How it Works, the chapter of the AA Big Book read at the beginning of thousands of meetings worldwide, it says, “Half measures availed us nothing. We stood at the turning point. We asked His protection and care with complete abandon.” I’ve been seeking these moments of complete abandon: methods of release, alternative ways of dying, places where the water can hold me up.

This winter in Berlin, I swam in indoor pools and went to saunas. I went to a swimming pool with a wave machine and was sloshed around with chlorine and 10-year-old boys. At Marek’s Saunahaus, the room was filled with fragrances of eucalyptus, sandalwood and juniper smoke. Afterwards, I rubbed my body with crushed ice. In the tiled, dome-roofed room at Stadtbad Neukölln, I immersed myself in a circular pool with water jetting from the mouth of a marble frog, the temperature of blood. I stayed in the sauna until my heart was beating so fast that my body panicked. I went out into the cooler air then, pointing toe first, into the cold plunge pool. Naked and submerged to the neck, pores contracting, my skin tightening and reacting all around me, it was like I was in an Orkney rock pool.

Now it’s summer, I’ve been following rivers and canals out of the city, on S-Bahn lines and cycle paths. Lake swimming is popular here, and I keep a list of places I have swum –Müggelsee, Schlachtensee, Grunewaldsee. I swam in a lake I later found out was meant for dogs. I swam in a pool in a barge floating in the river Spree and in the wonderful public Sommerbäder – open-air lidos with both heated and cold pools, for each borough.

In a Hinterhaus off a smart street, I was shown complimentary tea and a relaxation area before being led to a pyramid resembling a cheap science fiction film set. This was a flotation tank, otherwise known as a sensory deprivation tank, and was my capsule for an hour. I was left to shower and enter six inches of highly salinated water. It was saltier than the Atlantic, salty enough to hold my body. Unencumbered by clothes or furniture or floors or gravity, I lay back. The water was body temperature, so I lost any point of contact and the only sensation came from my body itself. I noticed twinges and tension and relaxed them out.

With my ears underwater, I could mainly hear my own breathing and heart but also doors opening and closing in the buildings and, every few minutes, a U-Bahn train rumbling deep below. I turned the lights off and, as the air above the water in the pyramid began to warm, my sense of location became indistinct. For just a moment, I had the feeling that my body was travelling, bullet-like, at great speed through space. I was like a baby in a womb and when the lights flashed on at the end of my hour, I was ready to be born, naked and dripping in saline.

When I got out, gravity was more of a drag than usual and I realised I was nothing but an addict, seeking drug-like experiences and different ways of altering my state of mind. I’ll drop 50 Euros on a float tank rather than a gram of coke and still feel the salt dripping down the back of my throat. But these bought experiences are often disappointing: simply paying and lying back waiting to be enlightened does not work. I want to confront and enjoy my senses rather than be deprived of them, and to gain the rewards of effort and imagination.

***

Often, on a Friday or Saturday night in the cottage on the tiny Orkney island where I lived alone for two winters, I wanted to be on a crowded dance floor in small clothes with sweat running down my back. I felt like an old woman before my time, beside the fire with a blanket over my knees, and missed the throb of the city and of nightlife. Lately, I’ve learned the German word “Fernweh” (literally, “distance pain”) which describes the feeling of wanting to be somewhere else, like a reverse homesickness (“Heimweh”), a longing for a place that isn’t where you are. I was struck by the word because I know how it is to be uneasy and never quite at home.

Now I’m back in the nightlife I missed, I am exhilarated, but awkward. Berghain is a cool place; I like it a lot – hard-edged, minimal and tolerant. The door policy seems to keep creepy men out. There are no mirrors anywhere in the club. For the first hour or so, I wander around, looking in the different rooms. There are “dark rooms” on the ground floor where people can meet strangers for sexual encounters. It started life as a gay club and heterosexuals take second place. I queue at the bar to buy Club-Mate, a fizzy caffeinated drink popular here. I roll cigarettes in the seating areas, watching couples talking. Their mouths are moving but I can’t hear what they’re saying, like underwater communication.

On the way in, the door staff put stickers over the camera on my phone. There is an open- minded attitude here to nudity, drugs and sex, yet taking a photo will get you thrown out. It’s highly refreshing that everyone’s not filming stuff. It’s hard for Internet kids, by which I mean it’s hard for me to have an unphotographed experience, but I am really here, more than ever. This is not a place for observers but for active participants.

After a while, I know I can’t stay smoking where different DJ sets, from the main room and the Panorama bar, jostle together uncomfortably. At some point, I have to let go and swim. I realise that after all these years, I still have the bass in my body. I drain my Mate bottle, take a deep breath and dance my way to the centre.

There is nothing to do but dive in. The dance floor is the seabed and I am scuba diving. My heart beats in time with the music, which builds in layers shot through with chimes, like sonar from a submarine or whale song. Earlier in the day, I watched a documentary about marine life and now its images – shoals of fish, breaching whales, curling waves – are swimming through my mind and merging with the activity in the club. The film was in French with German subtitles, reflecting the disorientation I feel in this city.

The Bajau people in the southwest Philippines live an almost completely seaborne life, in small boats and houses on stilts out to sea. Many never set foot on land apart from to trade, when some experience “landsickness”. The Bajau have physically adapted to an aquatic life, developing clear underwater vision, negative buoyancy and the ability to hold their breath for long periods.

It’s been exactly four and a quarter years since I last drank alcohol, a few months more since I took drugs. I stopped drinking on the spring equinox in 2011, shortly before entering a three-month rehab programme, and every equinox and solstice since then marks another quarter year sober. I like to celebrate these dates. As my body is moved by the brutal music, I think about where I've been on previous solstices – the top of a hill in Orkney, the stone circle, the Atlantic coast. A nightclub might be a strange place to celebrate a sobriety anniversary, but it’s been long enough that I know I won’t drink and I have unfinished business. I’m looking for a part of myself I left behind. I lost the active addiction but I don’t want to lose her, the tall brave girl with long pale arms and flushed cheeks. I’m chasing myself through the crowd on the dance floor. I catch glimpses of her white shoulders, her vibrating jaw, her trailing handbag. She’s always swimming away from me.

I take a break from the dance floor and, on a metal staircase, I watch the light fade on the first half of the year. The sky is pink behind the wholesale warehouses of Friedrichshain, behind a Mercedes sign and passing aeroplanes. I think about the tilt of the earth that creates seasons and solstices. I talk to a young gay couple, both coming up on ecstasy, who tell me about their polygamous relationship and that “Sonnenwende” is the German word for midsummer, then hug me.

It’s coming back to me – the half-remembered nights I spent, too many nights, wandering dim corridors, queuing for dirty toilets, waiting for the drugs to kick in. The nightlife I left behind is still there. Each weekend it’s filled with new groups of kids from suburban Melbourne or rural Iowa or Athens or Düsseldorf; students or call centre workers or rich kids. I’m dressed low-key in black trousers and T-shirt and don’t attract much attention. I see traces of white powder in the toilets and my heart aches.

I’m less angular now than I was when I was 25. But as I dance, the beat is shearing off the soft politeness, the regret and sadness, the silence and the longing. I’m not looking for sex or drugs, I’m looking for some kind of completion. It’s healing to remember the good times as well as the bad. I’m pleased I am still able to immerse myself in different environments – the city, the islands, on land and sub-sea. I can no longer have a lost weekend but I can lose a few hours. I can still enter the hatch to another domain and, to some extent, access those disinhibited, euphoric feelings. I want my imagination and words to recreate the sensation of an ecstasy trip, the waves, warmth and wonder.

It gets dark, I get tired. After three or so hours, being sober and alone becomes uncomfortable. It’s the shortest night and I always leave early these days. As I find the exit, I see the couple I met, dancing together with huge pupils and sweat-sheened skin. They don’t see me.

Leaving the club is like emerging back above water, into a colder brighter world I’d almost forgotten. The year has peaked, the solstice passed and 2015 is all downhill from here. It is getting light as I cycle home over the Spree. The sky is clear and the road is hard and I am landsick.

**********

Amy Liptrot's first book, The Outrun, was released to widespread critical acclaim earlier this year and was recently awarded the Wainwright prize.

***

Illustration by Daniel David Freeman