Dubious Heritage

by Heidi James

I am descended from a long line of liars, which is even less noble than it sounds. It’s impossible to trace my dubious heritage, though I suspect it goes as far back as the Roman Empire, or earlier still. It’s impossible to trace because depending on who you ask, my ancestors are: Italian, Indian, Jewish, Scottish, English, German, rich, poor, brilliant and ordinary. It’s difficult to follow the threads back. And so easy to exaggerate. I doubt it even matters, but it’s a weakness I have to keep in check if I don’t want to succumb to this unfortunate family trait.

It’s easy for one tiny lie to grow into a version of truth that obliterates a prior reality; then the best you can hope for is that the lie becomes fact. Which often times it does. Repetition is the lie’s fixative. We need look no further than our narratives of history, culture and religion to see the evidence of this; even science is a story told to explain and construct the world around us, as physicist David Bohm said, ‘What we take to be true is what we believe…what we believe determines what we take to be true.’ But at least science can be properly tested, which, let’s face it, most liars can’t.

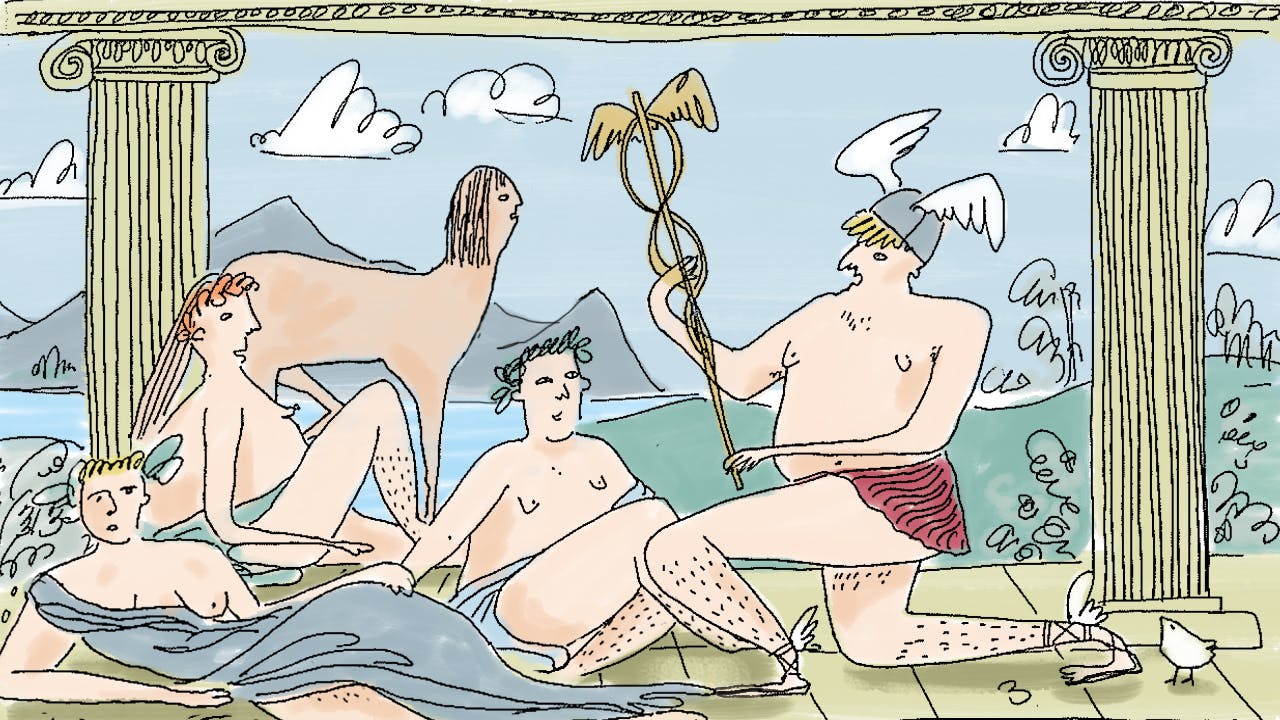

But to return to my point, I was born into a family of liars, and lying is as old as humanity. Early civilisations were experts in the art. From tellers of tales about the Trojan horse and Prometheus, myths and lies proliferate throughout history. Plato wanted to ban poets from his Republic, because he thought them to be liars – not that I care what that idealist believed. Liars in the Roman era had their own god, Mercury (or Hermes, in Greek mythology); he was also the god of business, eloquence, trickery and thieves. The god of hucksters and hustlers everywhere, his acolytes surely include: priests and marketers, advertising executives and poets, politicians (obviously), journalists and novelists, parents, children, teachers and lovers. He is the god of boundaries and those that cross them, the boundaries between true and false, alive and dead. He could navigate across the line safely. Most of us can’t. For most of us, being alive involves lying, and yet to lie is the death of intimacy, of knowing, it’s being dead to what is. That is the true liar’s paradox.

Mercury is also a heavy metal that runs and flows like a liquid, though it doesn’t dampen or soak what it comes into contact with; it resists, stands apart. It’s also highly toxic. It used to be called quicksilver; to say someone has ‘quicksilver wit’ is to say they are unpredictable, rapid, impossible to pin down. You see what I’m getting at? How the naming of this chemical element that slips through fingers when you try to grasp it; that is difficult to define, or follow, only highlights the collaborative web of deceit that makes up reality. The dancing back and forth. These connections in language, myth and physicality highlight the impossibility of spotting a liar.

There have been many famous liars, of course: Nixon, Shakespeare, Hitler, Ponzi, God, Satan, Clinton, Henry VIII, Matthew Hopkins; liars who change the course of history, who distort reality, make it or are it. Perhaps we could even say that there are some good liars, those who lie in order to expose the truth, like Alan Abel and his media pranks, or Jean Genet. There are so many different kinds of liars and different kinds of lies. For example, state- sanctioned lies and propaganda. Directing our collective hate and fear, spinning beliefs about the poor, the threat of refugees, terrorism, the nanny state, small government, profit, loss and monotheism’s promise of reward still to come. Then there’s Hitler’s Big Lie, which operates on the belief that the more incredible, the more colossal the lie, the more people are likely to accept it. For who would have the temerity to lie so brazenly?

But they are not our kind. Our kind only wages war on petty reality, our delights and terrors warping the world of a far smaller audience. Lying begins early (if the gene has caught, it can skip a generation and if it has one becomes an avid truth teller –also a kind of liar), usually in small ways: blaming siblings for misdeeds, inventing elaborate reasons for not doing chores or for failing at school, claiming the glory for saving a kid getting beaten up or a starving kitten - until one day, someone tells you they are dying of an incurable disease, and you grieve and you cry and do endless searches on the internet to see if there is any miracle cure, perhaps using powerful leaves grown only in the Andes and then they call a couple of days later and tell you that everything is all right, not to worry. It was a mistake. They misread the letter. The doctor wore the wrong glasses when he read the X-ray. It was the nurse’s fault, the social worker’s. Their bus was late. The printer had run out of ink, the cheque is in the post. You will hate yourself for being so naïve and swear you’ll never be taken in again, but you will be.

Why are we so gullible? The experts call it confirmation bias; we seek to believe, to stay comfortable, to confirm our preconceptions, to feel better, stronger. Who wants the truth? Especially if the truth involves a confrontation with ugly facts about brutality and suffering, or confirmation that we are ordinary, mediocre, that our arse does look fat in those jeans, that we will die and there is nothing out there to give us purpose or meaning. That everything is nothing, eventually or, at best, is a shitty bunch of atoms.

Other categories in the taxonomy of lies include hyperbole, histrionics, hypochondria. And optimism.

Why do people lie? There are the obvious manipulations: lying in order to achieve something, to get away with a crime. Lying to get a job, lying to save face, lying to avoid an argument. Some people lie for attention, or because they’re cowards. Some people lie to charm and entertain. But some liars are hiding a sterile emptiness inside, concealed behind layers of false selves, false selves created to comply with the expectations of others. These poor buggers are the result of mad, bad parents, of narcissistic mothers and fathers – the ultimate liars who look into the mirror only to see a reflection they’ve concocted and then coax their infant to return the correct likeness.

Consumerism is a lie, selling us what we don’t need by making us believe that we do.

Let me tell you about one particular person, or better to say, let’s use one person, and the many stories told about them and by them, as an example of how the liars in my family operate. We’ll say he was my uncle. He was a hero in the war, with scars of shrapnel wounds to prove it. He had shot down German planes over the English Channel, watching them as they spiralled into the sea. He could speak Japanese after being held captive in a prisoner-of-war camp, except he couldn’t bear to, as it was too traumatic. (He was born in 1947.) He was a medium who could speak to ghosts and once performed an exorcism on a house so filled with evil that it nearly killed him, but he managed to release the demon into an oak tree in the garden. He regularly spoke to his great-great-grandfather, dead for fifty years, who sat on his bed and chatted about football. He once stood in for Peter Bonetti, saving a goal against Sunderland – apparently there was a plaque with his name on it at Stamford Bridge – and he remains a hero among all true blue Chelsea fans (if they haven’t heard of him, they aren’t real fans). He taught Eric Clapton how to make an Old Fashioned using whiskey he had made himself. He was a millionaire twice, but the taxman cheated him each time. He told his sister he would push her down the stairs so she would lose her baby. He was an electrician and had done all the wiring in Buckingham Palace for the Queen, at her request.

Or how about this: my grandmother was the great-granddaughter of an illegitimate son of an Indian prince; she was a concert pianist; she was a great beauty and was offered a Hollywood contract on the ocean liner bringing her to England in the 1950s – which she turned down; she was the lover of an aristocrat who, on his vast estate, had built a folly with the skulls of his former mistresses, she escaped using a pair of stockings and a nail file. She was a secretary for a firm that made paper, she lived in a small town, was married with children, and had many secret affairs.

In my family they tell these stories about you, too, till you can’t know yourself. For example, they told me that I had a heart condition, that I was born covered in dark hair, that I was a genius, that I’d broken my arm in a fall, that my father was dead, killed by the IRA, that my mother had been in labour with me for a whole week, that I was simultaneously both a marvel and a shame. They said an uncle was a paedophile and even his wife almost believed it (no smoke without fire), they told a child that she was bad, and bad and bad and she definitely believed them. They told me I was a slut and had a lot to answer for, that my mother had men queuing up to screw her, so who could be sure about my father’s identity, although my paternal grandfather secretly cared and watched me from a distance as I was growing up. Like Santa Claus. Another lie.

He said, she said. They said.

And there are the lies you tell because you’re too scared to tell the truth, because you’ll be hurt, or lose someone’s affection, or they’ll leave. Because they lied to you and told you that you were only lovable if you lied.

I love you is a lie.

Yet another kind is telling your partner that you’re too stressed to listen to their opinion, it’s telling them they’re shouting when they haven’t raised their voice. It’s telling them you’ll kill yourself, because you can’t take the pressure of their disagreeing.

And another is being an absent parent. It’s a lie because conceiving a child is a promise, unwitting or not, it is a bond formed in flesh, and walking away breaks it; is an act of deception.

When you’re caught in someone’s web, it’s impossible to know what’s real, so you’ll understand why once I believed I was a horse. I don’t mean anything crazy, like in a past life or something. I mean I knew once how it felt to have only your senses and your legs. To not trust the world around you. That you could only run, that words would betray you.

Depressed people rarely lie, it seems they see reality with more clarity so perhaps lying is necessary for good mental health. Nietzsche said the lie is a condition of life; in which case to go on living we must be delusional.

The suicidal impulse is a liar; death won’t make you feel better.

Psalm 116:11 I said in my haste, all men are liars.

Doctors lie. Nothing will keep you alive forever. Or cure what’s really wrong.

Perhaps we lie to know the unknowable, to soothe ourselves with the comfort of answers against cold, howling mystery.

Overegging the custard is a form of lying. Purple prose, extravagant, overwrought language and so on; but then so is so-called straightforward, simple, ‘pure’ writing.

How do you know if someone is lying? Intuition – a sense of something not right? Testimony? Witnesses? Do you read their credit card statements? Their body language and micro expressions, a lift of the nostril? And what if they are right and your version, my version is wrong? My version is wrong. Am I even capable of perceiving truth? What if I am a horse, a thief, a malingerer, an ingrate with so much to answer for? What if I did steal all my dad’s money, and cause my mother’s life to be a misery? What if I did kill my guinea pigs? What if.

What if.

What if.

Perhaps I want the truth because I want to know the unknowable, I want to pin meaning down like a fact to a board. Perhaps it is me that is killing intimacy. Perhaps I am the liar. Perhaps I am totalitarian. Because all reality is fractured, limited, isn’t it? And maybe that is Mercury’s role, to guide me, us, over the boundary and back again, navigating the unknowable. But that trickster, unsettling the world –this world, seen like Argus Panoptes through so many eyes and perspectives –reveals only a world always beyond grasp.

If even science, our bastion of absolutes, only ever operates within acceptable error bars, or margins of fallibility that we can live with and is of course, reliant on our measurements, our technologies, our criterion – and by this I mean human creations, human understanding, human constructs –then what foundation for truth can there be? What is out there? Beyond us, beyond me? Was my father in the army? Killed by the IRA? No he isn’t, wasn’t, that’s easy to prove and anyway, that was my lie to explain his absence when I was little. My lie. Sometimes I wonder if I made up their lies to excuse my own. I wonder who is the origin of all those lies I tell? If you tell a lie, believing it to be true, are you a liar?

We are all liars. The white lie to save face, to save your job, to save feelings; the social contract depends on it. Our profiles on social media, those slippery curations of our selves, our best selves, our prettiest, most accomplished selves, our politically correct, elegant, good-tastes selves, our well-travelled, hip, authentic selves; all lies. You are a liar. I am a liar.

If I can’t know truth, then can I emerge from the lies as something else, something new? Unknowable, content in mystery? Then I am not a liar and nor are you. But I've gotten carried away, again, expanding on my premise, exaggerating, being pompous, showing off – more examples of lying.

But consider the world is flat, is round, God exists, doesn’t, the heart feels, it doesn’t, women are inferior, they aren’t, the sun revolves around the earth, it doesn’t. Animals are without language, dumb, unfeeling. Capitalism is the only solution, along with democracy. These are words and you understand them and you are reading them, which means that my thoughts, tapped out in a stuttering rhythm and deleted and rewritten are now encoded, embodied in your synapses, or so I think I read somewhere, which is another form of lying – the repetition of half-understood, half-heard facts. Conversation. Perhaps best to not speak. Or write. Or read. Or think.

***

Illustration by Polly Williams