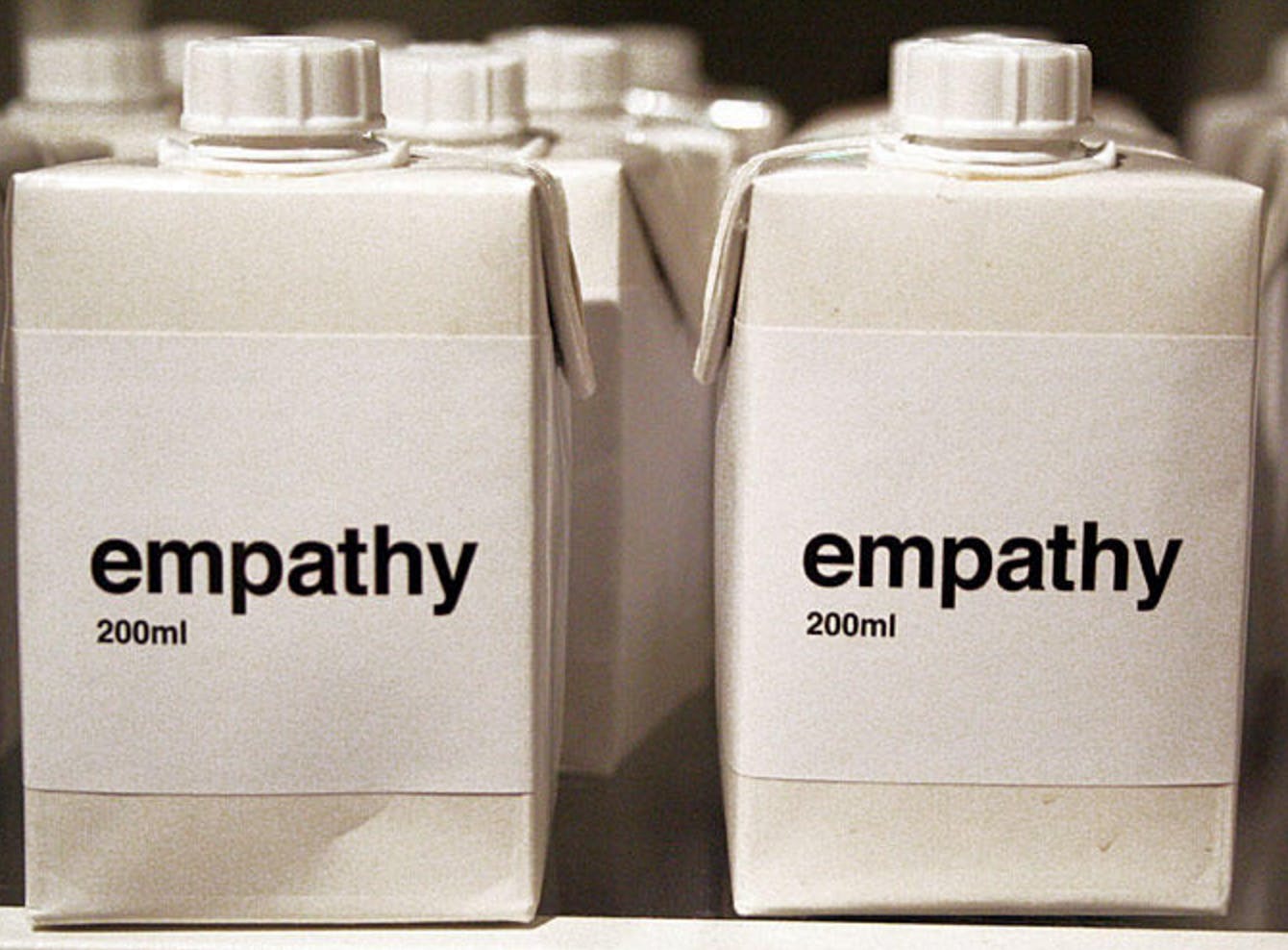

Choosing Empathy

by Annette Barlow

Empathy: the intangible architecture that supports our deepest connections; the unseen building blocks that help us to understand the needs, perspectives and motives of others; the ticket for a society racked with hate?

Ours are times of terror: racial tensions, escalating violence and flagrant bigotry masquerading as politics rampage through our everyday lives, and single-word utterances to describe devastating tragedies (Orlando, Dallas, Istanbul, Baton Rouge, Nice) have become all too familiar. In moments like these, our faith in humanity is profoundly tested; more than ever we covet a sense of community and togetherness.

It’s a natural instinct to look to our leaders (elected or not) to rally us as, for the most part, we learn early on that the people in charge (parents, carers, educators) will protect us, and make decisions that put our best interests first. And yet, Donald Trump’s “political” campaign continues to gain traction, its reactionary, hatemongering invective luring voters as if spoken by a present-day pied piper. Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage convinced Britain to vote to leave the EU through a despicable nationalist narrative that cast neighbour against neighbour; once the racist backlash kicked in, they washed their hands of the whole affair. American police target black men, shooters target American police, religious men target LGBTQ people, terrorists target the general public; our seemingly progressive, moralistic society is growing more combative by the day, and increasingly, difference is being cited as just cause for violence.

Dr. Emma Seppala, Science Director of Stanford University’s Centre for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, argues that “pitting us against others – terrorists, immigrants, liberals – creates a feeling of us against them. Ironically, this brings about a sense of in-group, togetherness, connection and belonging. By making broad statements about other groups, [these politicians] trigger a sense of in-group which gives people a feeling of security.”

Instead of creating a sense of unity through compassion and altruism, these politicians soothe our need for togetherness by defining and demonising otherness.

The more the lines of difference are drawn, the more volatile society becomes, and the more people suffer.

Could empathy – the simple notion of identifying with another person’s feelings – help to unravel the tapestry of self-serving egotism that our supposed leaders have woven? Can we choose to be empathic, and can that choice help to heal global wounds?

*****

Recent studies have shown that our empathy is dampened when it comes to people of different race, class, gender or nationality – i.e we find it more difficult to imagine ourselves in another person’s shoes when that person is visibly different from us. But key research also suggests that when we are able to identify with someone and can see the world through their eyes, we’re more likely to treat them with kindness.

So, under what conditions are we best able to identify with others?

Researchers generally define empathy as the “ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling,” and it’s a skill that by the time we reach adulthood, we should be well versed in. There are actually two types of empathy: “affective” empathy, which describes the sensations and feelings one has in response to other people's emotions, and “cognitive” empathy or “perspective taking”, which describes the ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions. Humans experience affective empathy from infancy, as they physically sense their caregivers’ emotions and learn to mirror them (positively and negatively). Cognitive empathy develops later on, at around three or four years old. To be clear: by the time we’re toddling, empathy is hard-wired into our brains. And it’s not just humans who learn empathy – numerous studies have shown that animals also feel empathy toward their peers, as primatologist Frans de Waal explains: “Our evolutionary history suggests a deep-rooted propensity for feeling the emotions of others.” If a monkey is able to actively empathise, then why do humans appear to be so bad at it?

One theory suggests that inhibiting empathy is a defence mechanism. People subconsciously limit their own empathic feelings in order to prevent an unbearable level of emotional flooding. According to one study (On emotional innumeracy: Predicted and actual effective responses to grand-scale tragedies, Journal of Experimental Psychology 44, 2008), “people overestimate the intensity of their emotional responses to grand-scale tragedies.” In this instance, participants predicted that they would feel significantly worse if thousand of people were killed in a disaster than if only a few were killed, but in reality, “they exhibited an ‘emotional flatline’, feeling equally sad regardless of the number of people killed.”

Another study (Escaping affect: How motivated emotion regulation creates insensitivity to mass suffering, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100, 2011) argues that, “As the number of people in need of help increases, the degree of compassion people feel for them ironically tends to decrease. This phenomenon is termed ‘the collapse of compassion’.” Simply put, people expect the needs of large groups to be potentially overwhelming, and, as a result, they engage in emotion regulation to prevent themselves from experiencing overwhelming levels of sentiment. In other words, “motivated emotion regulation drives insensitivity to mass suffering.” The key word here is “motivated”. Even if it is on a subconscious level, we make a choice to limit our empathic feelings in order to preserve our own emotional stability. But is it possible to bring that choice back into the realm of conscious behaviour?

A 2014 study published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Addressing the empathy deficit: Beliefs about the malleability of empathy predict effortful responses when empathy is challenging) thinks so. According to the authors, “Empathy is often thought to occur automatically. Yet, empathy frequently breaks down when it is difficult or distressing to relate to people in need, suggesting that empathy is often not felt reflexively.” However, their study showed that people who held a “malleable” mindset about empathy (believing empathy can be developed) “expended greater effort in challenging contexts than did people who held a fixed theory (believing empathy cannot be developed).”

Is a willingness to be empathic all it takes for us to naturally express more empathy? It would seem so. Study participants who held a malleable mindset about empathy demonstrated an increased effort to feel empathy when it was challenging, responded more empathically to people with conflicting views and spent more time listening to emotional personal stories of out-group members.

Simply by reframing your ideas about empathy – by opening yourself up to the idea that empathy is a choice, and a skill that you can improve – you change your willingness to engage in it in a variety of beneficial situations. Indeed, the authors conclude: “People’s mindsets powerfully affect whether they exert effort to empathise when it is needed most ... [and] this data may represent a point of leverage in increasing empathic behaviours on a broad scale.”

*****

So, we’ve learned that while our capacity to empathise is natural, our ability to practise empathy is autonomous. Whether or not we extend empathy to others is a choice, and the perceived limits to our empathy can change depending on how we choose to feel. Theoretically, it’s a weighty realisation – but theory won’t undo mass slaughter, acts of terrorism, bigotry and hate. We need action. So, how can the practice of empathy impact the world not only on a micro level (personal, local, individual), but also a macro level (public, collective, policy)?

By practising empathy, we aren’t just more able to demonstrate kindness to people we perceive as different from us. Rather, we’re able to change prevailing attitudes towards otherness. Indeed, studies such as Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatised group improve feelings toward the group? (Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Jan 1997) show that “feeling empathy for a stigmatised group can improve attitudes towards the group as a whole.” For instance, when people learn that empathy is a skill that can be improved, they engage in a more effortful way to experience empathy for racial groups other than their own. Not only that, but according to a study from the same journal (Perspective taking combats automatic expressions of racial bias, March 2011), “interracial positivity resulting from perspective taking [cognitive empathy] is accompanied by increased salience of racial inequalities.”

Allow me to just hammer this home: empathy (and the choice to practise it) reduces racism. It reduces prejudice.

And it’s not a stretch to apply these findings to other perceived societal distinctions: gender, nationality, religion, class, sexual orientation, age. The potential spectrum of improved interactions is far-reaching, and creeps into all areas of our lives.

Fortunately, including empathy practice in our day-to-day lives is surprisingly simple; prevailing advice suggests that five habits will develop our empathic skills.

1. Actively listen: listen intently when people speak to you. Show that you understand what they are saying. Respond visually, but wait to respond verbally until the speaker has finished.

2. Talk to strangers: ask questions; engage people in more than a cursory polite greeting.

3. Use your imagination: put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Imagine their feelings, senses, frustrations, joys. Try this with your favourite TV or literary characters.

4. Focus your attention outward: for an hour a day, focus on how other people feel, what they might make of any given situation, instead of thinking about your own feelings.

5. Meditate: take a quiet 10 minutes out of your day; go for a walk. Allow your mind to quieten down, and you’ll find it is much more receptive to empathic feelings.

*****

George Orwell wrote, “It is only when you meet someone of a different culture from yourself that you begin to realise what your own beliefs really are.”

What do we want to realise about ourselves? That we’re small-minded and hate-filled, so fearful and limited that our preferred modus operandi is to employ violence and intimidation? That we are bigots and racists, misogynists and homophobes? That we’re better than everyone else, and all “others” deserve to pay – with their lives? Their freedom?

Centuries of social progress stand to be undone as the world’s elite manipulate the masses into delivering their global vision: division is currency, and these people know how to spend it.

We have autonomy, and we can make a profound choice every day. Choose to project into the world the energy we’d like to receive back. Choose compassion.

In the wise words of Jason Marsh, founding editor of Greater Good, “Empathy without a moral code is futile. But a code without empathy is dangerous.”

***

Photograph by Creative Commons