How Should We Be Bored?

by Ellie Violet Bramley

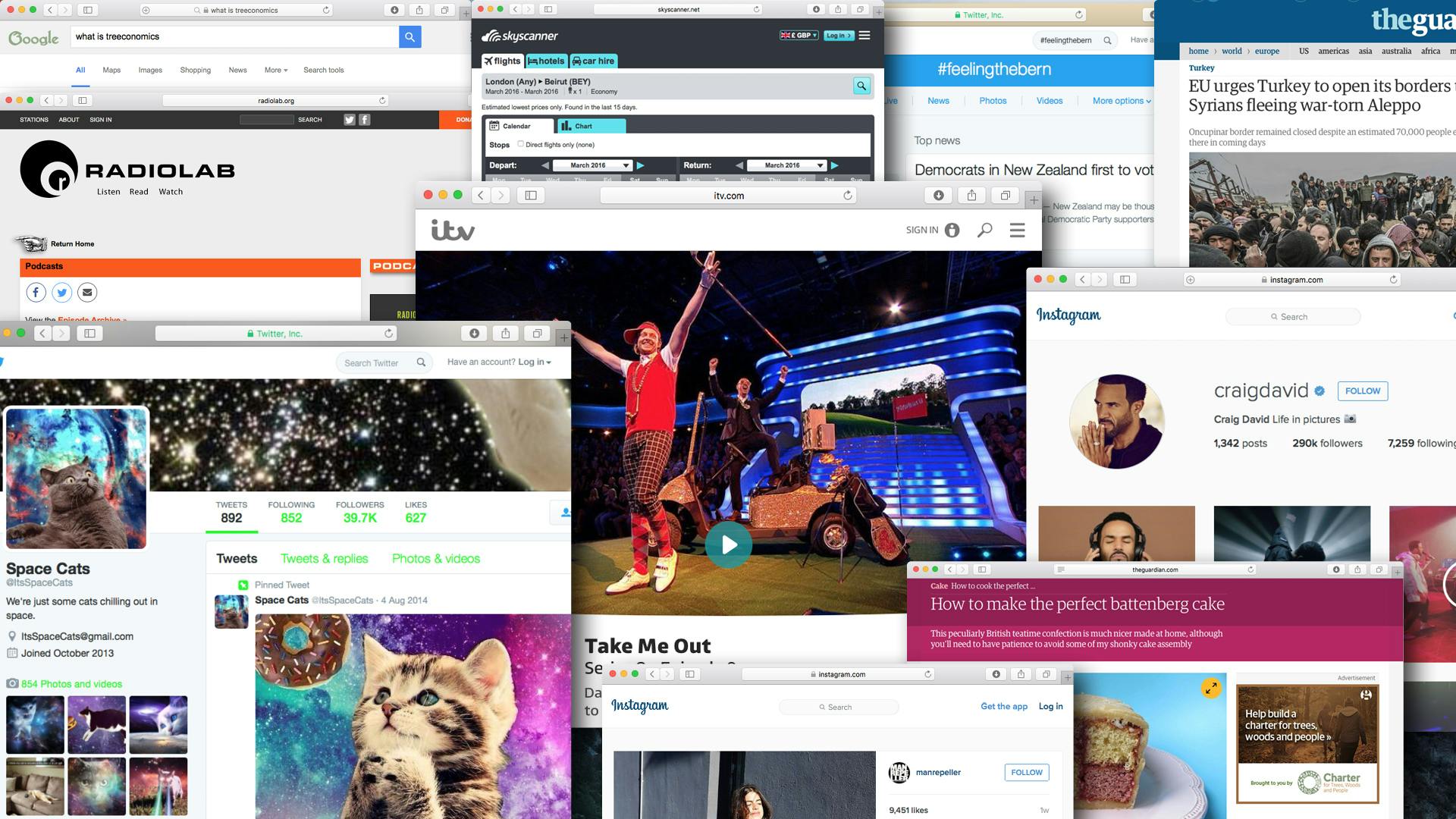

It’s a lazy Sunday afternoon and I’m watching Take Me Out on catch-up. It’s a cringe-y lol and the right level for my brain, ticking to a slower tock after too many gin and tonics last night. Except I’m not just watching Paddy – “let the angel see the delight”; “let the jal see the frezi” – I’m also on my phone. I’m checking what kimono Man Repeller’s wearing over which floral flares, and what pearl of #blessedwisdom Craig David is offering on Instagram. I’m seeing who’s #feelingthebern on Twitter and which sweet fat moggy is being sent flying on a pizza slice by @ItsSpaceCats. I’m seeing how Felicity Cloake recommends making the perfect Battenberg and which border is now closed to fleeing Syrian, Iraqi and Afghan refugees. I’m What’sApp-ing a friend a 10-strong list of emojis translating as ‘last night was fun’; I’m emailing a colleague to say ‘yes, I can definitely get that to you first thing’; I’m texting and asking my sister to play squash next weekend; I’m Googling ‘what is treeconomics?’; downloading the latest episode of Radiolab; reading about Scalia and seeing how much a flight to Beirut would cost.

Except I’m not just doing all that, either, because the book I’ve been reading for over a month is open at my side, stuck on page 428, which is where I’ve been for a while because I have to keep skipping back to remind myself of the characters’ political allegiances – and who the hell is William Adler again? I keep picking it up and putting it down to water my cheese plant.

The amount of information and entertainment I can, and do, access is dizzying. And yet I find myself sighing and feeling, dare I say, a bit… bored. Except Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, declared boredom a thing of the past years ago. These days, this “state of permanent receptivity”, as sociologist Georg Simmel described it in his 1903 essay The Metropolis and Mental Life is the norm for anyone living in a culturally rich conurbation. “We are under constant assault by ‘interestingness’, as new-media aficionados,” wrote Evgeny Morozov in a piece for the New Yorker in 2013 entitled Only Disconnect.

And it’s in the context of this hyper-connected reality that a type of nerve-y inattention, often brought on by information/entertainment overload has, to my mind, blossomed to become one version of modern boredom (with the obvious caveat that it’s one hugely privileged version). A grimy kind of boredom – frazzling, but with a residual sense of guilt.

Boredom is a tricky beast, not least because it’s tied up with our sense of self. Tolstoy called it the “desire for desires”, Marie Josephine de Suin “the fear of self”, Schopenhauer “the reverse side of fascination” and Saul Bellow the “conviction that you can’t change” as well as the “kind of pain caused by unused powers, the pain of wasted possibilities or talents”. In The Pale King, David Foster Wallace wrote not only a book about boredom, but also one that intentionally inflicts boredom on the reader – “sometimes the important things aren’t works for your entertainment,” he said.

Boredom has many guises and different hues when diffracted through the prisms of culture, religion and language. “The thought that someone would care to be alone with their thoughts is culturally positioned”, says Malcolm McCullough, Professor of Design and Architecture at the University of Michigan, who recently wrote a book called Ambient Commons: Attention in the Age of Embodied Information. “Yankee Americans have that deep,” for instance, “Ralph Waldo Emerson and such – among my people it is a great tradition to go into the woods and be alone with one’s thoughts.” In the tradition of Emerson, a solid sense of self is the signal goal: “What lies behind you and what lies in front of you, pales in comparison to what lies inside of you”, he wrote.

A while ago, when talking to David Mitchell on Radio 4, Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology at MIT, Sherry Turkle, described boredom as brain-ordering time, time to “build up a stable sense of your autobiographical self”. Time, then, to get your head in order when your thoughts might otherwise be dispersed amongst the gazillion other things going on around you, IRL and online. Time to find the solidity of self that Emerson thought so precious. From that perspective, perhaps boredom can become a tonic to a fractured identity, key to the assimilation of a self where the discrepancies between “the true you” and the version of you that you think you are, are at least somewhat narrowed. Time spent learning to be settled and discerning rather than app-flicking or paying attention to everything that crosses your eyeline.

Turkle’s idea of restorative boredom fits a narrative we now hear as commonly as the old one that links boredom to idleness and a lack of personality. While the frustratingly superior (and incorrect) adage states simply that “only boring people get bored”, in recent years the mainstream media, rather than decrying boredom, has been celebrating it. Where once it was something to shun, now it’s something to “lean in” to, the “last privilege of a free mind”, “our encounter with pure time as form and content”. But it’s definitely not the kind of boredom I feel, my focus spread thinly – “no likey, no lighty” – and my interest never allowed to take the deep dive that could lead to fascination (the antithesis of and therefore, surely, the antidote to boredom).

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang, author of The Distraction Addiction, views the fashionable sort of boredom as an opportunity rather than an “absence”: the “‘emptiness’ of boredom like the open space in a modern art gallery, not the emptiness of a box of cookies with only crumbs left.” The other, nerve-y kind is what, he explains over email, perhaps happens when “stimulation gets numbing”. Take it to its extreme – hopefully way further along the spectrum from zoning out of dating shows – and you reach The Rich Kids of Instagram, where, he says, “people tend adopt a ‘yeah I'm on the Gulfstream, ain't no thing’ attitude.”

But how can boredom be both nervous, inattentive energy and soothing, contemplative calm? Perhaps psychology can provide an answer. John Eastwood is a clinical psychologist at York University, Toronto. His scientific definition of boredom – though he’s keen to stress there are others and that boredom studies are still in their infancy – looks, for one, at what the conscious experience of a person is when they’re bored. “To be bored is to have an unfulfilled desire for satisfying, meaningful engagement or activity,” he explains over Skype. It’s a state in which there’s a fundamental discrepancy; “that juxtaposition of the desire and the lack of fulfillment of that desire.” Anchored in the self rather than the external world, it involves a “disordered sense of doing and this associative feeling of being disengaged from meaningful activity or internal thought.”

And with it comes a disordered sense of time, with minutes and hours seeming to pass slowly – time, it seems, really does fly when you’re having fun. This rings particularly true of the kind of childish boredom for which I now, as an adult, feel a hazy nostalgia. Days spent blowing Hubba Bubba bubbles and sucking Push Pops could feel unendurably long – the summer holidays felt mammoth.

Talking to friends about boredom, I found that not a single one didn’t almost immediately associate it with being a teenager, too. And here is where Dr Eastwood would link the concept of constraint – “a person having to do something they don’t want to do” – with boredom. “Young adulthood,” he says, “is characterised by lack of power but a lot of adult desires, so you’ve got all the capacity to be an adult but you’re not given the ability or permission.”

This, again, is not a stabilising boredom. But every coin has two sides, and from the cognitive state of boredom can, says Eastwood, come the “impetus to meaningful engagement or productive expression of the self” – clearly some productive contemplation came from all those teenage hours, lying on your bed, listening to Semisonic, staring at posters of David Duchovny and trying to figure yourself and your place in the world out. So, perhaps not in the unpleasant state of cognitive boredom itself, but on the other side, are lurking the moments where we allow ourselves the room for contemplation; solace and salve for a fractured self.

It’s in these moments where Eastwood’s and Turkle’s takes, though seemingly contradictory, can, with “a little more nuance”, marry. As the former puts it, “if we’re constantly being stimulated and entertained and titillated from outside us, I agree that we never have the capacity to know an elaborated autobiographical sense of self.” And so “we need moments… and then we need to be able to sit with those moments and not freak out with boredom… we need to be able to use those moments to figure out our desires, passions, voice, where we fit into the world in the next 30 seconds and in the next five years – how can we express ourselves.” The impulse might be to turn on Netflix, or YouTube but, he says, that “may not be a good solution – they may obliterate the feeling of boredom in the short-term, but we maybe haven’t had any deep long-term response or solution to the signal that is being provided by the experience of boredom.” Turning to Paddy McGuinness might be good for a brief lark, but it’s at the expense of time to think about bigger life goals, to make life more broadly fulfilling, and my sense of self more complete.

These moments are not, as Soojung-Kim Pang puts it, “a missed opportunity to enjoy yourself” – when you start thinking of them as such, that’s when you re-enter the state of agitation, of unfulfilled desires, and therefore become bored again. They are not the times you should start to wonder whether you’d be better off listening to the latest Serial. “It's an invitation to relax the mind, to mind-wander, as psychologists call it – and in that state, to let the mind do what it does it best: make associations, turn over problems without conscious involvement, and sometimes have creative ‘ah-ha’ moments.” This is why, he says, people like Neil Gaiman declare their love of boredom, because it “represents an opportunity to expand the self and exercise the creative mind”.

But all too often these moments, in this world of aggressive “interestingness” – where we are both blessed and, seemingly, cursed by a wealth of things to read, look at and listen to – are filled. Professor McCullough, speaking over Skype from his armchair, describes how people have become “accustomed to the constant stream of stimulation, of micro rewards – human beings are hardwired to want incoming messages and to see bright flashing things in their peripheral vision”. “Naturally,” he says, “there’s some over-consumption going on.” I squirm a little in my chair – though a fan of technology, I doubt McCullough would approve of my afternoon spent ricocheting between media streams.

If, instead of checking for message notifications and flicking through pictures of astronaut cats, we can access “the kinds of attention that flow,” where attention doesn’t need to be paid, it just happens, “then your whole disposition, your sensibilities alter and you become less vulnerable to this stimulation stream.”

Flow is often described, explains Eastwood, “as occurring in moments of peak performance, in athletes or artists. It’s a sense of being so immersed in an activity that you lose all sense of yourself… of time – the do-er and the done become merged in the doing.” So it’s in these states, the antithesis of cognitive boredom, but akin to Turkle’s restorative boredom, that we may find a completeness. And it’s in this terrain that mindfulness also finds a home, as through the non-intellectualness of immersing yourself in the sensory, you are erasing the potential of cognitive boredom, with its angsty, unfulfilled desires, to frazzle. When you’re in that edgy boredom, explains Eastwood, “you are judging the moment, you’re saying ‘this sucks’. It’s actually a very adversarial, hostile way of being.”

But how do I squeeze these beneficial gaps into everyday life – those moments that Emerson would be proud of, that Turkle would value as time to build a stable sense of self, that Eastwood might consider the positive outcome of the impetus of boredom? For Eastwood, to stem chronic boredom as individuals, “or as a culture, or in this historical epoch” we need to address how we “implicitly view the self” – “as a vessel to be filled, rather than as a source of meaning”.

So, I’m going to turn my attention away from the piña coladas of the Isle of Fernandos, to refrain from pinballing between Craigy D and Supreme Court judge obituaries, to sit awhile and not do. “To recognise,” as Eastwood puts it, “that it’s up to me to animate the world… and that engagement animates the world and gives it colour and excitement and vitality.” And all this will render the future doing, the fun and the thinking, in ever brighter Technicolor.

***

Illustration by steve shaw