Why Today's "Lonely Crowd" Should Let 'Life Stages' Go

by Alex Taylor

What was your New Year’s resolution? Research shows the most common commitments are health- or body image-related. But in truth, these are simply different ways to express the same desire – a craving to better fit society’s mould. And yet despite our best intentions, less than 10 per cent of us achieve our targets – the most ardent lasting a month. We overwhelmingly fail, say psychologists, because we hastily strive for insurmountable change, rather than steady progress. Perhaps this explains why “getting organised” sits third on the list, a telling, catch-all phrase of loose, bugging dissatisfaction.

The craving for societal respect is as old as humankind, but its form has been ever evolving in the post-war era. Britain’s Generation Y now resembles the “lonely crowd” that sociologist David Riesman spoke of when defining young, post-war Americans. Noting the era’s psychology of abundance, he explained how unheralded affluence had caused America’s youth to develop an “other-directed” personality. This meant the approval of peers, either those “known or indirectly acquainted, through friends and through mass media” became the barometer of success. As a consequence, Riesman found “close behavioral conformity” became the norm through “an exceptional sensitivity to the actions and wishes of others.”

For today’s twentysomethings, the “lonely crowd” analogy fits perfectly. Yet far from pushing ahead, as the bubble of post-Cold War ’90s euphoria foretold against a backdrop of D:Ream’s ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ and Blair’s Cheshire cat grin, we cannot even get a grip on the ladder. Instead, for the first time in a century, the Equality and Human Rights Commission warns that this generation will be worse off than their parents.

But if we are the failing generation, we are also the failed generation, stymied by housing and job markets spiralling out of control. According to the Intergenerational Fairness Index, incomes of twentysomethings have rose by 1% from 2013 to 2014 while house prices increased by 2.8%. The average wage for the age group is just over 22k, a gaping 16k below than the 38k needed to attain a mortgage for the average house price.

David Cameron’s “starter homes”, aimed at easing the first-time buyer burden, look set to do the opposite. According to charity Shelter, you’ll need to be earning £50k, rising to £70k in London, to afford one. No wonder we are generation rent. And even that lifeline is thinning, with costs in the capital already averaging well over £1,000 a month.

Ours is the age of anxiety.

A big part of this tension stems from expectation hangover. Born in the ’90s, we internalised the decade’s assumptions and aspirational values; a new age of technological opportunity and political hegemony. We sailed into our futures motivated to make a difference, but disembarked in a ghost town. We are left to pick at the scraps of the dot-com beneficiaries and their baby-boom subsidisers.

Workers aged 21 in 1995 were paid an average of 40% more in real terms in their first 18 years of employment compared to those aged 21 in 1975. The picture has now reversed and youth unemployment is at its highest since 1992. Getting qualifications doesn’t seem to help, either. One in four graduates found themselves unemployed in 2012, racking up £40k worth of debt for the privilege.

In theory, this state of affairs could free this generation from certain expectations. But sadly, the reality is very different. A noticeable divide remains between the haves and have-nots. As “other-directed” personalities, we compare ourselves to the generation before us and feel fearful of failure, especially when looking at the obstacles ahead.

To compensate and suppress anxiety, we are clinging on to “life stages” for definition. Studies generally show twentysomethings drinking less, smoking less and experimenting less than those before them. In the words of one Durham University professor Fiona Measham, “the generation before Generation Y were bar hopping, binge drinking and taking cocaine. Now there isn’t that frenzied drunkenness. There’s a new sense of sobriety among young people.” Although avoiding drug binges is not necessarily a bad thing, the point is still valid: risk aversion is the overriding compulsion. Living wild and free is seen as a guilty pleasure distracting from the grind of unpaid corporate internships.

It is no surprise, then, to see small-c conservatism rising amongst today’s youth. There is a trend for alternative views to the status quo to be shut down by prohibition on demand, as evidenced by the recent outcry over Germaine Greer’s speaking at Cardiff University, following comments judged to be transphobic. Rather than engage in debate and demolish her arguments – as you’d hope students might – their immediate reaction was to call for her removal. A wish not granted, as it turned out.

In this light, the urge to compartmentalise life into stages of behaviour makes absolute sense, not just in line with Riesman’s theory, but as a way to assert some level of control at a time when feeling helplessly cut adrift is common. Social media, Riesman’s new age “mass communication” plays into this, hurling peer-pressured messages of conformity at us. Someone else is always having a great time, celebrating their dream job or in a new perfect relationship. And it’s right in our faces, begging for a response.

The hollow nature of this world was revealed when, earlier this year, teenage Instagram model Essena O’Neill dramatically quit social media. In a lengthy post, she exposed its fallacy, explaining: “It’s a system based on social approval, likes, validation in views, success in followers. It’s perfectly orchestrated self-absorbed judgement…exploited by advertisers and companies.” A fitting mirror for the “other-directed” personality type.

What these social media pictures don’t show are the fingernails dug in to the tightly held hand of your partner. Or the aching muscles from the forced Instagram smile. The details which reveal that no matter how hard you try, you cannot conjure the reality of a happy life by acting out social normalcy. These life stages do not fit all. Nor should they; you must make your own.

Essena also spoke of her fear upon rejecting her lucrative source of income. She had “no idea” how she was going to make money from now on, but knew she wanted to “use my imagination, my individual mind, my unique take on this world.” This can equally be applied to the life-stage conundrum, and lays bare another paradox – at a time when we are desperate for order, guidance and direction, and are busy trying to impose this on ourselves, in many ways we are living in a more liberal, tolerant culture than ever before. In fact, if we can get over the state of flux induced by judgement paranoia, we can find more freedom than ever.

A friend, Immi, recently made this clear to me, proudly proclaiming she had become a “life choicer”. I asked what this meant.

“I was set to tick off several of the big life stages by my mid-to-late 20s,” she explained. “I was in a committed long-term relationship and at the start of a promising career, even if buying a first home in London still seemed like an impossible mission.”

This seemed as close to 2015’s compartmentalised, life-stage dream as possible. However, she couldn’t ignore the fact that “even though I was on course for completing that checklist, I still felt like I wasn’t achieving as much as others I knew of a similar age. I knew I could do and be more. So I made some drastic decisions, threw off any presumptions of what I should be doing at ‘my age’, and now I’m having the best time of my life. I still have long-term life and career goals, but I’m putting less pressure on myself to meet those at a certain time or age.”

Immi won her battle of personal role confusion, deciding to prioritise herself ahead of society’s aspirational framework. This can often be more difficult for women, given the motherhood question. Many I spoke to knew friends keen to move out of the parental home, have kids and be settled long before 30. But “life choicers” like Immi have been able to gain a broader perspective.

Another female, twentysomething friend of mine attributed her outlook to the influence of her mother, who by having her later in life, showed that it was possible to define yourself outside family life. For that reason, she has been career-focused, but recently packed in her job to go travelling with the money she saved living at home. Again, the need to find personal fulfilment outside corporate culture snuck up and forced her to break free. She admits, “I do feel as though friends think it’s about time I moved out, but I have the bonus of being able to save and hopefully buy a place within the next five years, whereas friends renting aren’t able to. Things will happen when they are supposed to.”

Life is to be lived, not restricted and sanitised. It is only through experiences both positive and negative that you can find out what you want in life. As this voyage of personal identity awareness progresses, so will your skills, talent and ability to achieve in other areas. Life stages will complete themselves, the more rounded you become.

And so what of my New Year’s resolution? I didn’t make one. My resolution stands whatever day of the year it is. Keep finding and cementing my identity, socially and professionally and everything else will fall into place. Age-related life stages pale in comparison to the importance of attitude.

It is worth remembering what became of the Cold War generation analysed in The Lonely Crowd. Tensions over appearance and reality consumed the ’50s, as generational post-war struggle ran riot. Parents battled in vain to reassert the values of the past in an ever changing world, while youth demanded progression and revolution with aplomb, spurred on by James Dean’s howled “you’re tearing me apart” to his father in Rebel Without a Cause. These seeds of discontent blossomed in the ’60s, producing some of the most radical mindset shifts of the century. Given the threat of atomic destruction, there was no time to live life in stages. This current age of anxiety is comparable in its fluctuating generational value. It’s up to us to make sure something productive comes out the other side.

***

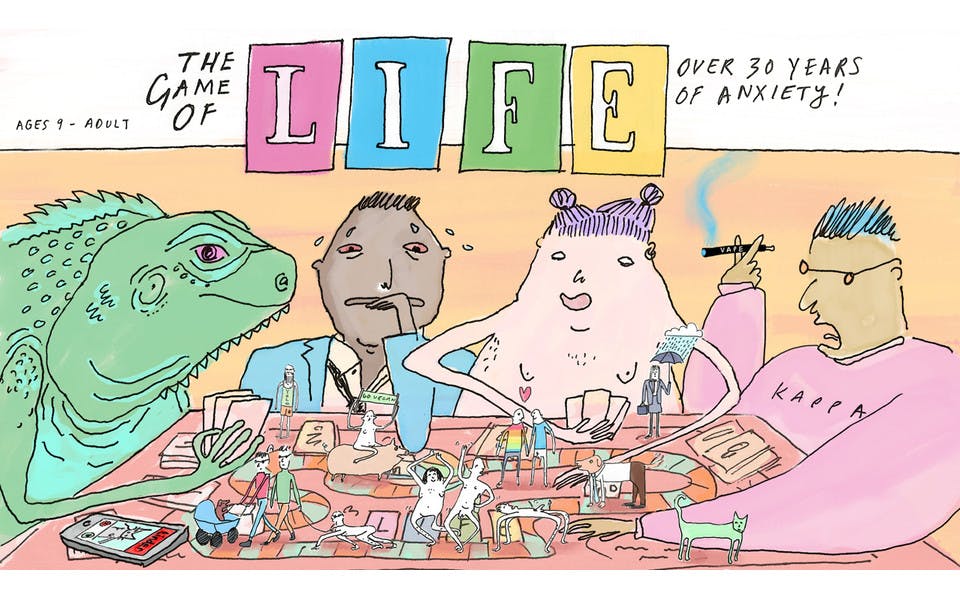

Illustration by Polly Williams