On Facing the Motherhood Dilemma

by Mish Way

A few years ago, I didn’t think making a family was a part of my future. I had just been asked to be in my first film. The director (who has since become a good friend) met me in a celebrity-infested West Hollywood restaurant, where we knocked back hard booze and talked about her film. I was new to Los Angeles and renting a room in a friend’s house. I was touring with my band non-stop, my copper IUD tightly in place, fighting off sperm. I was dating a man I was starting to love, but everything felt just as it was – selfish and up in the air.

The director invited writer, entrepreneur and self-proclaimed asshole, Gavin McInnes to join us for dinner. After a few hours of making jokes about all surgeons having Asperger’s syndrome, and a bunch of other stupid shit that was so funny I don’t even remember it, we went outside to get our cars. McInnes immediately started in on me about children. He’s a father of three and infamous for his views on feminism’s obsession with women’s careers. One of his video segments on Rebel Media warned the women of New York to get out of the city that has become “an elephant’s graveyard for their ovaries”.

“I just think moms who stay home with their children don’t get enough credit or respect, but feminists insist on twisting my words,” he wrote, as an introduction for viewers of the video. “Sometimes this makes me lose my temper (as you’ll see). But I have kids and I want everyone to share that experience. Is that so bad?”

Outside of the restaurant, I lit my cigarette and McInnes asked me if I planned on having kids. I shrugged, “Probably not. I’ve got a lot of things I want to accomplish.” He shook his head and looked at me like I just told him I was spearheading the conspiracy group that thinks the world is flat. He laid into me about the importance of families, children and how feminism has ruined the pride of motherhood. I listened and controlled the urge to roll my eyes. Why should I bring kids into the world? I thought, as he went on. I’m barely wealthy enough to take care of myself. What about my life? The director slapped McInnes’s arm and shut him up by changing the subject. I hugged them, got in my car and drove home.

Later that year, that man I was falling in love with proposed to me while we were in Alabama, at our friend’s motorcycle shop. I thought he was taking me out back to give me a bump of coke, but instead, he got down on one knee. We got our own place in Los Angeles soon after, were married the following year and all those “things” I still wanted to accomplish slowly started to take a back seat to new desires.

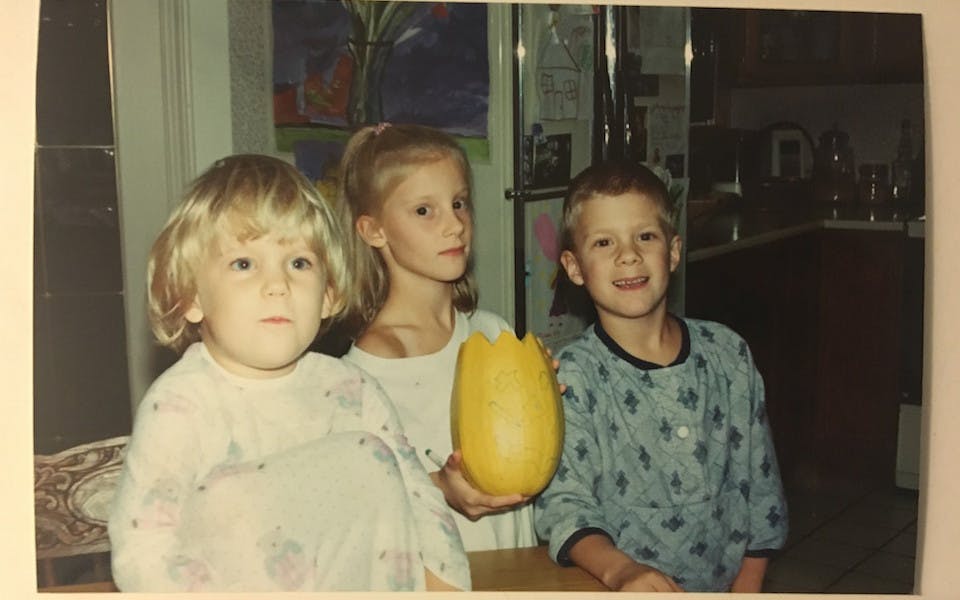

I’m the oldest of four siblings. Both my parents have five siblings each. I come from a line of obnoxious, loud, and very drunk Canadians on one side and hard-ass but charming Polish stock on the other. Every summer of my childhood was spent with my brother and sisters and our troupe of cousins, aunts and uncles on the family farm in Masonville, Quebec, running around in the fields, catching frogs and making a mess as our parents smoked pot and cigarettes and made fun of each other.

Our house was always loud, especially at family dinners, which got so insane that sometimes you had to clap your hands like a moron just to get the response to your question. But I love my siblings, even if my brother ratted me out for having parties when my parents were gone and my sisters stole my clothes and cut off the hair of the Barbies I passed down to them. I was the hardest child of the litter, fighting with my father constantly until I left home at age 17 and distance mended our embarrassing bullshit. I always looked to my mom and her sisters when I was little. I watched them slug wine and laugh so hard at their inside jokes that one of them always admitted a little pee came out. Now, I realize that I’ve taken the cycle of family for granted. And that I want to contribute.

For some of you, motherhood won’t be an issue by choice. For others, it will be genetic, not voluntary. While a bunch of Millennial readers will think my understanding of what makes a “woman” is grossly conservative. I don’t care. This is my dilemma. And maybe some others share it.

No one in my peer group of aspiring musicians, writers, artists or professional drunken idiots has children, except for my very close friend, Shelby. She and her husband have two little boys. My husband and I flew up to see them on the farm they recently bought in northern Canada. It was a wake-up call for my husband, who has been threatening to rip my IUD out with his teeth for the last six months. Every time I’m with Shelby and her kids, I leave in awe of her. I had lots of boyfriends throughout my twenties, but they were just as selfishly driven as I was. Today it’s rare to meet a middle-class man in any urban area who, at the age of 25 or so, has the sole aim of starting a family, of being a father. I remember years ago when Shelby’s husband came over to measure my wall, to possibly build me a new storage unit. He said, “Shelby and I have the same goal. We just want to make a family together. That’s it."

Your twenties are meant for screwing around – messing up, dating frivolously and figuring it out. Dr. Helen Fisher calls the courting process of Millennials “fast sex/slow love”; we meet at bars, fuck through Tinder, and jump into bed the way our grandmothers jumped into the financial security of marriage. Fisher believes we are moving towards a lifestyle that mimics the shared parental responsibility of our hunter-and-gatherer past. However, there is also an increasingly delusional, fame-hungry, selfish and socially singular state, which is heralded as the epitome of success by popular culture and validated by social media. There is nothing singular about being a parent.

In a recent lecture in Brazil, dissident feminist scholar Camille Paglia talked about motherhood. Paglia approaches a woman’s reality with some actual scientific reality. My feminist education had me ignore “my biological clock” like it was some evil invented by an oppressive male. It’s not. Becoming a mother is social, but giving birth is biological. And only people with a uterus can grow human life inside of them. That being said, as women have decided to focus on careers over motherhood, the determinations of our biology have caught up to us. Fertility declines with age, and parents have less energy the older they are when they begin. Although there is new technology on the rise that may help older women have healthy births, this kind of advanced science is only available to that lucky, stinking rich 5 percent.

“In 1970, only 1.7 out of 1,000 women were having their first child between the ages of 35-39 years,” reported Business Insider, quoting findings from statistical analysis released by the USA’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention last year. “By 2006, that rate had increased six-fold to 10.9 women out of 1,000… In 2012, 11.0 out of 1,000 women were having their first child between the ages of 35-39.” However, 85 percent of births in the USA in 2013 were still to women under the age of 35. Whilst in the UK, 2014 research quoted that, for the first time in history, the average age of a first-time mother was 30.

“The issue of the relationship of a professional woman to motherhood is a huge issue. I can not think of a bigger issue facing women [today],” Paglia said. “This is why I have called for young women, age 14 to 15, to be presented with [the dilemma of motherhood], which I think every woman must process.”

I don’t know if I would have been able to predict my senior years as a teenager. I was too busy painting my nails with glitter and smoking weed out of apples, but if the dilemma of my later life had been presented in a pragmatic way, would it have made me anxious? Or, would I have laughed it off, like any other part of the school curriculum?

Paglia goes on to say, “The problem comes when we try to harmonize a woman’s laudable, professional desires for her creative powers [with motherhood]: she wants success, she wants visibility in the world, and yet she may also want children. Young women should start thinking about this early on [in life]. Teachers should say to them, “Imagine your life at the age of 45, 55, 65 and 75. How do you imagine your life at that time? Do you want children or not?” If a woman wants to marry and have children in the middle of her college education, she should not be scolded for doing that.” Paglia, a professor herself, suggests a university system that allows pregnant women to continue their education whenever they see fit. “There should be no sense that she is somehow shaming the cause of feminism by making a choice for children.”

I never thought I wanted a family, because I had not yet met the person I actually wanted to make a family with. If I had been asked to declare my intentions at school, as Paglia suggests, I would have been presented with a dilemma I was not ready to face. Even later, at 27, when McInnes asked me about kids, I wasn’t there yet. And that’s the crux of the problem: women might be getting there later in the game, but our biology is still running to a social system we have grown out of. Women don’t get pregnant at 25 as often as they used to, yet their bodies haven’t changed. Men can pump out effective sperm into their later years, whereas a woman’s reproductive organs have a different shelf life. Maybe that is unfair, but that is reality. That is science. The female is entirely responsible for bringing a pregnancy to term. This is the superior power of being a human incubator.

Paglia went on to talk about the increasing happiness of working-class women who started families early and were not afforded the luxury of becoming stylists. “They have earned less and do not have the social visibility of middle- class women, but they have greater happiness in the final decades of their lives as they age, because they see their grandchildren and the children of their grandchildren and they have the sense of being a part of the continuity of life.” At a certain point, my career stopped being so important. In fact, all those “things” like great recognition for my music or writing started to seem kind of fucking stupid. I want more. A musician I know just went on tour, 7 months pregnant with her baby girl. You can do both.

Personally, there is nothing more depressing than the idea of laying on my deathbed, my husband already long gone, with my only legacy being a bunch of links in the pages of Google, knowing I did not conceive not because I could not or wholeheartedly did not want to, but because I believed that being in Vogue magazine was more important. Upon retirement, no matter how big a CEO someone becomes, how many fine restaurants they get to, or how many great articles they have published, they will be forgotten almost instantly. Someone new will come in to take the job; the information they created will become dated and be overwritten. But no one can replace the role of their parent.

I don’t expect everyone to feel this way. I’m also someone who over thinks before making big decisions; I want to be prepared for everything, but with something like childbirth, I have to let go and realize there is only so much planning you can do. My husband and I are already a family. If we never have children, that will be enough. However – and I never thought I would ever say these words – I want to try.

***

Photograph by Mish Way