One Hundred

by Huw Nesbitt

The other day, I had a nightmare. It was Wednesday afternoon and I’d been up since the night before writing a newspaper review of a translated science fiction novel called One Hundred by the Portuguese author Priscila de Araujo Severo. It’s about a detective who has an accident that leaves him with the power to see the future, without the ability to change it. The plot was good but the writing was full of bad metaphors and had the solemn tone of someone who had never realised that nothing is funnier than unhappiness.

❖

I finished the review and emailed it to my editor just after lunch, then sat down with a beer, had two sips and immediately fell asleep. At first, I was having quite a pleasant dream: I was a session musician with a chest tattoo of the Virgin Mary participating in the centenary celebrations of the life and works of the Italian communist avant-garde composer Luigi Nono. For some reason, I kept leaving my wallet in the fridge and during a performance of Nono’s seminal opera Intolleranza 1960, I sang in the choir while wearing a biker jacket and drinking American whisky.

❖

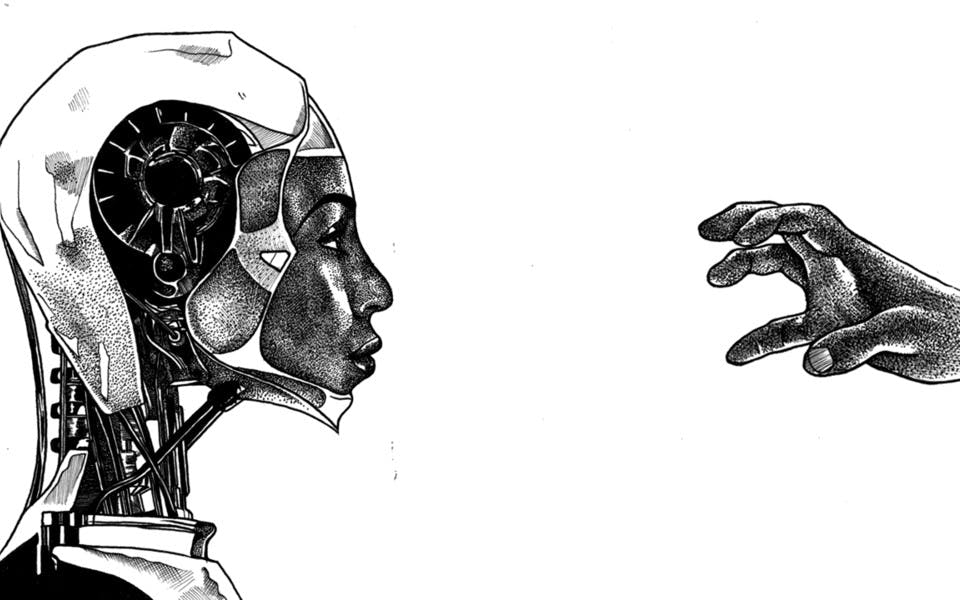

After this, the nightmare began. I found myself to be the detective in Severo’s novel and things were bleak: I was on trail of an anonymous serial killer who was murdering cyborg sex workers on a space station the size of New York. Just before every murder happened, I’d have a vision of it taking place, but I never got a chance to see the culprit’s face because every time I reached the scene, they’d already vanished. There was also a subplot in which I became the best Texas Hold ’Em player in the galaxy, but that faded as the body count rose and my boss threatened to fire me unless I brought whoever was responsible to justice.

❖

In the end, it turned out the killer’s identity was staring me right in the face. It was I who was, in fact, the murderer. I’d been killing hundreds of cyborg sex workers during psychotic episodes triggered by a post traumatic stress disorder that was caused by my accident, which is why I had no memory of any of it. Despite this, I was sent to prison for life. The visions kept on happening, but I was no longer sure if they were real or the product of my disturbed psyche. I would see lots of things: the last episodes of soap operas, people locking themselves out of their houses, the conclusions of World Cup football matches; the rise of a wretched country that exalted the works of Martin Amis as the pinnacle of literary accomplishment.

❖

I didn’t like prison very much, but I got on okay. People knew I was an insane murderer so they left me alone to spend my time reading and writing and going to the gym. Then, one lunchtime, I met a man in the corridor. He appeared lost. I noticed he was blind and carrying a white cane so I asked him if he needed help. “I have something to ask you,” he said. “I have come from the future to grant you a wish. If you could have any superpower what would it be?” “Immortality,” I replied. I have always wanted to be a famous writer and they say the greatest authors live forever through their works. “OK,” he said. “So now you will live forever.” And then he disappeared.

❖

With hindsight, I’m not sure if this was the best superpower to choose, or that immortality is really a superpower at all, but by that point it was too late. Living forever had its ups and downs. I saw people I loved grow old and die and once-great civilisations disappear like they had never existed. History seemed meaningless and the bravest attempts by humans to create order and dignity were frail and prone to perversion and violence. Thankfully, after a couple of hundred years, they let me out of prison and I had plenty of time to dedicate to achieving literary immortality.

❖

Following several failed attempts, I eventually wrote a prison memoir that was hugely successful and read in thousands of different languages for millennia. However, once the universe had ended and all life became extinct, I realised that literary immortality was actually a vain and hollow ambition. That said, once everything had ceased to exist, my problem with being able to see the future solved itself as the rest of time appeared to be an infinite present in which nothing ever changed.

❖

After that, I woke up and found I’d spilled beer all over my lap, but the events of my nightmare got me thinking about literature. And, dear reader, after boring you with details of my dreams, it feels apt to confess my sins, too: recently, I’ve been taking creative writing classes. And what’s more, I’ve enjoyed them, a lot. Nonetheless, the one thing that’s bothered me is when people say, “Write what you know”. Along with, “Show, don’t tell,” and “Find your voice,” it’s one of the gospel-and-verse laws of creative writing. But if, as another saying goes, fact is often stranger than fiction, then where does that leave us? And since dreams obey a logic that cannot be comprehended, are they even stranger still?

❖

The other day, I had a dream that literature was an infinite puzzle and that it wasn’t humans that gain immortality through writing, but books themselves. And that even if the world did end, they would carry on being read forever in the minds of people that enjoyed them, whether they were alive or dead because this activity takes place somewhere that’s outside ordinary time and space – a place in which words are no longer what they seem, but a vast network of shifting signs that indeterminately refer to one another, like sand being blown across the desert through a corridor of mirrors in the imagination of a being who cannot tell when they are asleep or awake.

❖

And then I woke up and found I’d spilled beer all over my lap.

***

Illustration by Daniel David Freeman