I'll Start with a Line

by Melissa Hutton

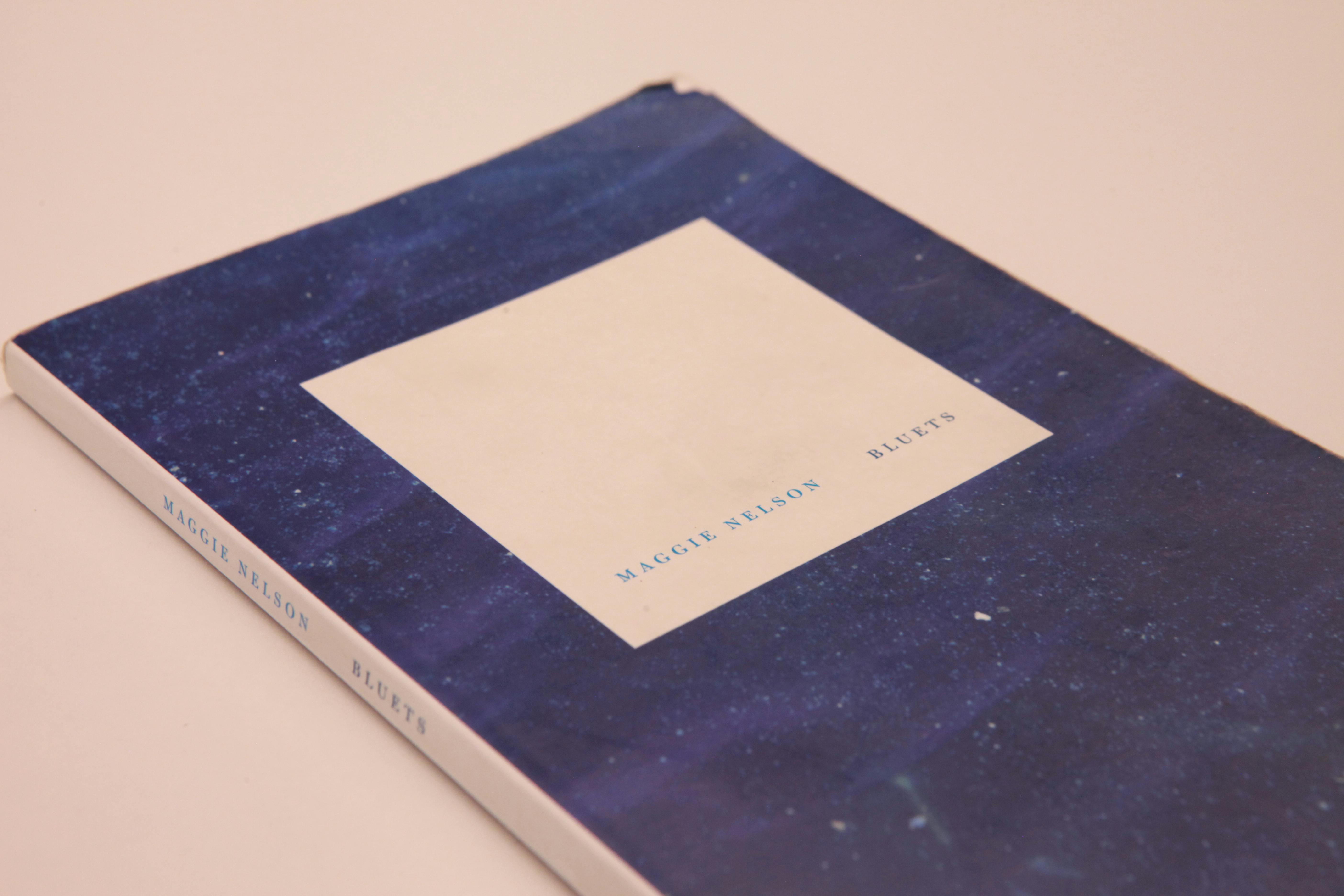

I got my first tattoo the weekend before my 22nd birthday. I decided – while sitting on the floor of a bathroom stall that I should’ve been cleaning, at the job I worked full-time when I wasn’t in school – on the word “bluets”. Or the title of Maggie Nelson’s lyrical talisman of a book. It was only later that I found out about its cult-object status. It felt like I had inscribed myself into a community, that which I had been seriously lacking.

I had barely finished reading Bluets for the first time. Mostly on the subway, mostly crying. Nearly bursting as I read, “75. I have been trying, for some time now, to find dignity in my loneliness. I have been finding this hard to do.” My sister sent a photo of the tattoo to my mum. At our next party, I was pulled upstairs by my aunts to pull down my jeans so that they could see the ink below my hip. I told them that it was a flower and the title of a book I had read a bunch of times because they expected an explanation. I told them that it was something I liked for a while because I thought that would make sense. Reading it once had been enough.

I’ve re-read it since having the title word drawn into my skin, in that black ink that looks blue, and I still think it’s a special book. Other people do, too. But getting the tattoo wasn’t entirely about Maggie Nelson’s pretty blue paperback. Bluets was something else. Maybe I say that to feel less creepy, but it marked the time and the place. Bluets was the time and the place. It was the point of a constellation, which, according to art historian George Baker, is something that can be “endlessly shifted, endlessly reconstructed, endlessly seen anew.” Bluets was endless. Mostly, it was a group of letters I thought I’d like to run my fingers over.

In his introduction of Paul Chan: Selected Writings 2000-2014, George Baker writes about Chan’s engagement with language and art. He writes about constellations as a foundational concept of Chan’s writing. Constellations as they pertain to the organization of knowledge and belief, reason and unreason, and to the creation of an image or a moment. “The labor of language, the work of writing, had become for Chan the endless production of constellations, which I would immediately characterize as thought or the idea erupting into a form that involves multiplicity, into a shape that creates new arrangements, into a set of unexpected relationships – into, indeed, visual images.” It is through the juxtaposition of unexpected or seemingly dissimilar ideas that Chan forms his constellations, that he makes images visible. This is very appealing to me. With the act of reading and writing comes the connection of disparate objects and with that, clarity and a shape, tangible and impermanent.

During the time leading up to bluets, my sky was small and the constellations dimly lit. Making themselves visible with such rarity that I often found myself staring into black, feeling panicked. I had been reading since I begged my mum to teach me at 4 years old. But it wasn’t until 20 that I started reading books that informed each other and my feelings, and started to map out something, although I didn’t know what. That was also when I sat down and tried to write for the first time since elementary school.

I’m inclined to agree with Eileen Myles in thinking that writing is desire, not a form of it. Being told that I could has never been anywhere near enough. I am a woman with want, so it’s something I have to deal with. I developed this reflex of repeating, in my head, “To desire is to be unquiet/but my desire’s to be silent,” from Elaine Kahn’s Women in Public – a terrible mantra. (Now, during better days or moments, “It keeps getting better”, à la Christina Aguilera, takes its place.) I didn’t want to seem like I wanted to do it. The writing itself was too embarrassing a display. I started taking creative writing workshops: uncomfortable. It felt unnatural to be sitting in a circle, everyone exposed, passing around secrets on 8 ½ x 11” sheets of paper. I obsessed over the body language, feedback and forced intimacy of these circles. I tried to say things. I felt bad as often as I felt good about receiving positive feedback. I couldn’t relax, or accept anything at face value.

I wanted to do something, nothing crazy, because I generally find that I’m lacking in anger and ambition, but something. I knew something required discipline and time. But I realized I couldn’t do anything and be at ease in more than a small, temporary way. Like the way we see a constellation. The image flashes in front of us or in us and then we lose it. The more we read or look with intent, the more often we see them, the longer and better we’re able to focus on distant connections. It was around this time that I realized reading and writing were about moving. Staying busy and unsatisfied, except in small and temporary ways. Letting in and allowing the moments that felt good, dizzying, clear and connected if for no other reason than that they tended to be few and far between.

After getting the tattoo, I felt involuntarily defensive while reading any criticism of Bluets. I had spent 22 years with this persistent, self-effacing loneliness; was nearing the end of my undergraduate degree and feeling aimless and had just experienced a prolonged sense of desire for another person – at times returned, at times not, and ultimately not – for the first time. It was undefined and disarming. I was unequipped and unhappy. Bluets was the most beautiful thing in the world. But I still somehow felt turned off when people had, inevitably, different readings of it.

My behavior fostered unhealthy isolation. Caused by the kind of negative reinforcement that is invited by caring about nothing more than being liked. You pretend to care about participating, cultivating interests and making connections, but you don’t. Not more than you care to be mirrored, agreed with and echoed. (Which is occasionally necessary.) You can’t mirror an image that isn’t there and as Paul Chan writes, “A voice that desires a reply sounds different from an echo that wants attention.” Echoes are empty by design. It’s through reading, I think, that I try to quit my bad echo habit and piece together a voice made out of desire. I’ve always envied and been attracted to people who have other means of feeling, learning and speaking. People who are a bit more in the world.

In an interview with Sarah Nicole Prickett, Maggie Nelson talks about not caring. She says, “I think there’s a kind of feminist not caring which is a little different from campy not caring which is different from a nihilistic not caring.” It’s different than not caring about being liked. That comes with having interests, things, people and realizing that if you’re a woman, you’ve been trained to want admiration more than you need it. But Maggie Nelson’s feminist kind of not caring pairs well with that. It’s caring about what’s been presented to you, but not if it means having to abide by it indiscriminately. Recognizing terms of living, negotiating and communicating that have been established and not bothering to give them your undivided attention if they don’t agree with your reality – if they don’t feel good. Which requires trusting yourself to discern what feels good. That is the kind of not caring that I’m approaching. Or that I think I’m approaching. That I want to approach.

In his essay Miracles, Forces, Attractions, Reconsidered, Paul Chan writes about art, its attraction and its natural repulsion of the advances of those who want nothing more than that which can be embraced, related and understood. Art, in this sense at least, can be synonymous with life. It is natural and necessary to be embraced, related and understood. It’s a means of survival for both art and people. You may or may not encounter repulsion or develop a self-esteem that plummets when you act in a manner that seeks nothing more than to gain acceptance or that prioritize this need over all else. This is a constellation. I was beginning to notice it as I was slapped in the face and called enigmatic in a watered down and disfigured sense of the word by someone who I let crawl into my bed out of habit. Not at the same time, although it might as well have been. He wanted me to know that the trying part was the ugly part and that it was showing. He could see it. He repeatedly tried to fit me into some category of Moody Girl Who Majors in English and Lives in New York. Everyone’s a stereotype to someone, although you shouldn’t be to the one you’re fucking. He thought he was an exception. “I don’t claim to be anything,” he said, hands out front, warding off attack but not from me, anyway. He wasn’t talking to me. I continued to dig into my pint of ice cream.

That night reminds me of another one of Chan’s ideas: Communication ≠ connection. Connection is something language dreams about. Connection is only glimpsed through language. Like when Maggie Nelson writes, “10. The most I want to do is show you the end of my index finger. Its muteness.” Connection doesn’t need all these words. This, is communication. This is me wanting the work I’ve put into being a person to be actualized. To be looked at. Acknowledged. This is me watching myself cry in a mirror after putting on make-up and sweatpants that make my butt look good.

In How it Feels, Jenny Zhang writes, “Why are some people’s feelings so repellant and others so madly alluring?” We repel what we don’t empathize with. The opposite of empathy isn’t the incapacity to feel, but a defensive willingness not to. We evaluate what we empathize with before we do. Sympathy is greeting-card easy, but empathy is a means of identification. You’ve got to be in it to be empathetic. On a really base and unexamined level, empathy is aspirational. An expression of feelings too close to ours that evokes the impression that we “could’ve done it ourselves” lends itself to repulsion. We want all of our big emotions to be displayed in something more attractive or deserving than us. Or if not in something more attractive or deserving, that it all be kept at a distance (in the sympathy or spectacle zone). That way, it’s safe to look. It’s reality TV. Of course (!) this is me wanting to be alluring. Do my references connect my ideas? Do they indicate that I’ve done more than sit around and think about my feelings? Do you find reading sexy? Is this me trying to be less repellant? Or is repellant not the right word? (Is this nothing more than imitation?) How much of me even wants to be touched? How much of me is willing? CAConrad, who The Believer awarded in Fall 2015 for being “the most sensible lunatic” the poetry world has, writes, in ECODEVIANCE: (Soma)tics for the Future Wilderness, “when public/toilet seat is/warm from/previous ass do you/become comforted/or leap off/in fear?” My favorite litmus test of self-exposure.

When my therapist recommended her list of depression/anxiety self-help books (which is not where I found Bluets) I winced, helpless. I nodded and told her I would look them up. That night I found a pink ticket slapping the windshield of the car that I was spending more time parking than driving. My sister came over and sat in bed with me while I cried ugly, loud and empty. Melodrama had never felt so natural or necessary. Bluets was something I grasped onto during a period when I didn’t eat, regularly panicked in class, cried in front of coworkers and was in constant search of consolation. Nelson writes, “27. But why bother with diagnoses at all, if a diagnosis is but a restatement of the problem?” I needed, among other things, for my problem to be restated. I needed to hear it back to me, in bits of research and poetry. Bluets was healing by iteration, an experience that wasn’t mine and didn’t need to be, in a language I felt and wanted to learn from.

The next time I wanted someone, he saw my tattoo and I immediately offered him the book as if to say, “Look! This is mine. Have it.” I thrust it at him because I finally had something to thrust. I was talking and it made sense to him and to me. It looked good. Being with him was like reading my astrological traits (constellations, look at that). I liked his take on me. Full, thoughtful and aligned with ideas I had of myself. It made me talk more. He actually said, “You’ve got a lot to offer”. Isn’t that the point of astrology? With him I expressed loneliness, longing and insecurity because he liked me sad. I indulged in it. Fanny Howe ends her novel, Famous Questions, with the lines, “Not him, not the reassurance he gave me but truth, or whatever you want to call it – that is, the meeting of two people who share one story and agree on its meaning. That’s what I’ve always been looking for.” It wasn’t the reassurance of meeting someone who talked me up that felt good. What felt good was letting myself be something. I performed a version of myself with him. And for the most part, for a moment, we seemed to agree upon what it meant. I didn’t lie on my back and play mute, blank, disinterested, or dead. I didn’t wait for him to say go. Or maybe I did, but then I didn’t stop. I relied on his understanding as special because it was and I needed to. I hadn’t ever done that before. It started fast and ended. But I saw it and I touched it. When I lost it, I panicked. But the sky wasn’t empty black. It was filled with stars. I picked up a book so I could seek new shapes.

***

Photograph by Riley Lombardo