To Be Good

by Heidi James

‘D’you want a hand with that?’ he says, a hand-rolled fag hanging from the corner of his lip, unlit, of course.

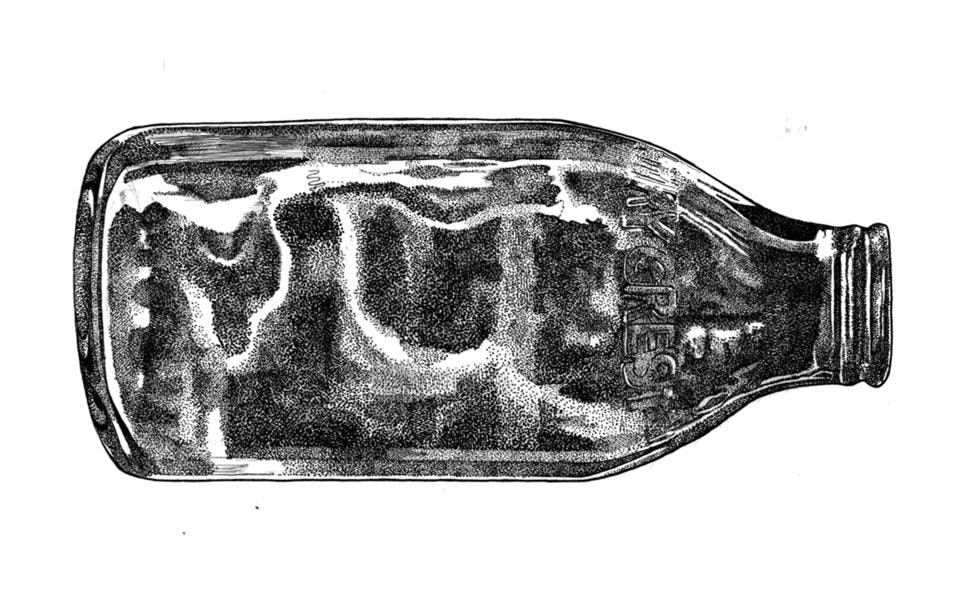

She pushes the crate of milk bottles onto the flatbed of the float.

‘Don’t often see a lady doing this job.’

‘No?’

‘No.’

She heard that in her last job too, brayed at her over champagne glasses and shiny table tops, in a building constructed of metal and concrete, glass and wood – all deadly, eventually, their fatal edges hidden beneath glossy surfaces.

He waits for a minute, standing, watching her as she checks the load against her order book.

‘You don’t say much.’

*

People, she’s noticed, seem to feel the need to point that out to her. ‘It’ll do you good to talk, you should go for counselling,’ Sofia, her sister, said last week. It was Sofia’s birthday and she’d made the effort to go to her party. ‘Just a small lunch gathering,’ she’d said. There were at least 20 people standing around in designer jeans and pressed shirts, drinking bottles of organic beer and the women all seemed to have tanned skin and slim ankles. Funny, the things she noticed. Things she wouldn’t have noticed before. Or maybe she would. ‘You need to live in the world again,’ Sofia had said when she’d found her in the rickety old summerhouse, perched on a pile of musty foam cushions, her feet resting on a cracked cricket bat.

‘What do you mean?’ she’d said, pressing her thumb against the pulse nudging in her wrist.

*

‘Right then, see you,’ She climbs up into the driver’s seat.

‘Yeah,’ he nods, then returns to the cubicle office in the corner of the depot.

The electric motor whines as it pulls the van forward and out into the street. It’s like driving a bumper car, only less fun. The blue dark falls open around her as she drives; her round is at the edge of the town, where the new houses bite into the old meadows and patches of trees. For a little while she is the lone human out on the road, her only company the rabbits that kick through the low orange beam of her headlights and the pointed slink of a fox that watches as she passes by. Cold, like the back of a metal spoon, presses against her cheeks. It soothes her.

*

‘I mean, why are you still delivering milk? With your qualifications! Why are you hiding away? This is the first time we’ve seen you in months.’

The party was over. She was washing up. The soapsuds broke the light into oily fragments on the back of her hands. Her vision contracted and then expanded. Sofia continued, ‘You’ve got a second chance, you’re one of the lucky ones. It’s time to trust people, the world, again.’

*

Luck, that’s what people call it, luck. But that is because they don’t know what it took to get out alive. The instinct for survival, blind panic. The vacuum it creates where nothing holds true, where everything is up for grabs. For some of us, at least, not everyone. There are heroes. There are people who turn back and help, who suppress the urge to get out and away, no matter what. But not all of us.

She pulls over and checks the book. No changes to the orders, no surprises. She gets out and grabs three bottles of milk and a loaf of bread from the van and walks up the drive of the house. The gravel grinds under her boots like broken glass and metal. She moves on, steady. The dark softening and opening, almost day, but not quite, neither one thing nor the other.

The paper described her as one of London’s leading financial analysts; they also misspelled her name and referred to the bombers as Pakistani, when they were born in Chester. They listed all the dead; their names in solid type next to their photos. She thought she recognised a few of them, the ones she climbed over to escape, the ones she’d left behind, perhaps still alive. Perhaps. Memory is a tricky substance.

*

‘It’s so rare, what happened. You have to learn to trust again, to live. You’re alive.’

She said nothing, thinking only of her life now, her small habits. She stacked the clean plates on the rack as Sofia watched, biting her lip, her expensive but tasteful earrings pinching her tender flesh.

How could she tell Sofia that she doesn’t trust herself? That she’s protecting the world from what she is? No one wants to hear that, the coward should keep their mouth shut and make amends. Why would anyone want to hear the coward’s side of the story?

*

There’s no running. She walks, milk bottles in hand, up each path to the door of each house and replaces the empties with the full bottles; she returns to the float, puts the empties in a crate and collects more milk and repeats the procedure. She walks. Walking. In the dark she ran – stumbled, more accurately – away from the silence, away from the heat, broken glass and metal grinding under her shoes like gravel.

*

‘Anyway, I’m so glad you came, I’ve missed you.’

‘Me too.’

‘It hasn’t been so awful, being here today, has it? Oh, don’t pull that face. I just want you to know I care.’

‘I do know; I just need space. And no, this hasn’t been awful,’ she pulled her jacket over her shoulders, turning to go.

‘Let me help you, please,’ Sofia said, as she held her close at the door. Sofia’s husband was with them, his face arranged to look concerned and patient. Sofia was always good and kind. She had been their father’s favourite, and why not? ‘We love you, Alison.’ She nodded, patted Sofia’s arm and walked away, exhausted.

*

People are beginning to wake. The tall, balding man who runs every other day is holding his heel against his buttock, stretching. A light aches in a kitchen, and a woman stands drinking coffee, looking out. She is nearly finished; soon she can go back, drop off the float and go home. She will be able to sleep through the day, through people and life and heat and light and dark and danger. And she will try again to be good.

***

Heidi James is the author of Wounding.

***

Illustration by Daniel David Freeman